Based on: Sarah A. Lanier’s book Foreign to Familiar. McDougal Publishing: 2000.

“When living in Europe, I carried a day-timer divided into half-hour blocks from 7 am to 7 pm. There was a page for each day. If a meeting came up, I would check my day-timer. It would tell me whether or not I was free. My pages were pretty much filled up, and I moved from one appointment to the next. When I lived in South America, I had a page for each month, and those pages were mostly blank. Yet my days were full as I looked back. They were filled with spontaneous events or routine events that didn’t need a daytimer as a reminder.”

~Foreign to Familiar by Sarah A. Lanier

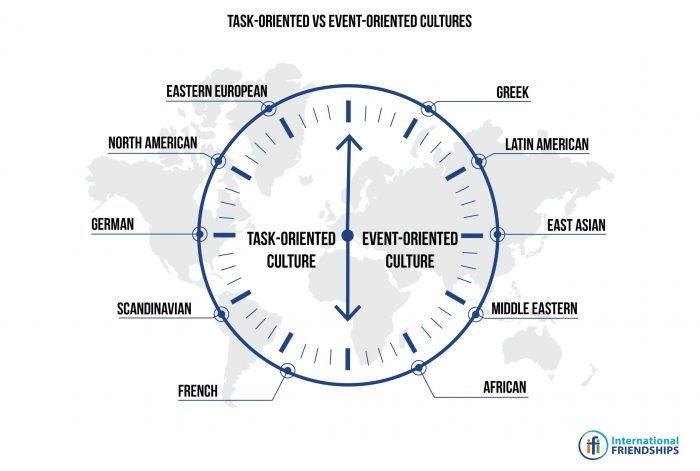

In the United States, the clock is an important part of each day. A sense of order helps society to run more smoothly and time has been recruited to provide that order. This time (or task) oriented society is common in many other cultures including Germany, Norway, and Canada. With time keeping them on track throughout the day, time can essentially be “saved” and used in another way to complete more tasks. However, there are also many cultures in which people are more event-oriented, in which saving time is not as important as experiencing the moment.

![]()

The book, Foreign to Familiar, by Sarah A. Lanier, paints a clearer picture of the many differences between cultures, including how most cultures can be split into one of two categories related to time: either a task-oriented culture or an event-oriented culture. Tension can be created when two cultures with differing concepts of time try to work or meet with each other. When event-oriented, spontaneous, cultures become too easy going and only react to life, they may miss opportunities to save money and avoid crises. However, when task-oriented cultures create too much importance and reliance on plans, they could miss great opportunities for experiences and relationships that may have happened outside of the time crunch. With neither type of culture having the “correct” way of using their time, both the task-oriented culture and the event-oriented culture have something to offer and something to learn from each other. By learning about perspectives of time from other cultures than your own, you can help create an understanding and balanced atmosphere when hosting, meeting, or even just interacting with internationals.

Indirect Vs Direct Cultures

As you may recall from a previous article titled 3 Characteristics of an Indirect Communicator, indirect and direct communicators have two very different approaches to communication. When adding in the element of time, the differences become more transparent. Most indirect cultures fall into the category of an event-oriented culture, a culture that emphasizes friendliness, and a dedication to making sure everything is phrased in a way not to offend. In the same sense, direct cultures often fall into the category of a task-oriented culture, one in which the goal is to have accurate and quick communication in order to respect time.

“Indirect cultures have the reputation for always being late by the direct culture people, who are viewed as being neurotically time-oriented by their indirect culture friends”(Pg 110). Each culture’s way of communicating can be directly tied to its own separate concepts of time. For direct cultures that value saving time, honest, direct, and accurate communication is esteemed so that tasks may be efficiently finished. Whereas event-oriented cultures value good relationships and focus on being friendly and inoffensive, no matter how much time it may take. As pointed out in the 3 Characteristics of an Indirect Communicator, getting accurate information from an indirect communicator (event-oriented culture) often requires asking through a third party. This takes up much more time than simply asking an individual what is needed to know, thereby frustrating a direct communicator (task-oriented culture) even more. In order to effectively communicate and complete tasks without frustration, both the task and the event-oriented cultures must strive to understand the other and create a balance between the two.

Time Savers Vs Time Users

For people in the United States, and others in a task-oriented culture, saving time is one of the biggest values. The saying “time is money” showcases just how much that is true. The goal is to plan the job in advance, be efficient, and get the job done. Task-oriented cultures enjoy using time efficiently and try to plan their days (almost to the minute sometimes!) so that they will be able to fit the maximum amount of tasks and activities into each day. When those in a task-oriented culture have a meeting or an event, a time is set for when the event will happen and the people involved are committed to being there, ready to go, at that specific time. This is true even for casual meetings between friends. To keep people from a task-oriented culture waiting after the set time is to say “you are not important, so your time is not important. I don’t respect you or think you have anything more important to do than wait for me.” If you were late to a meeting in a task-oriented culture, apologies would immediately be made upon arrival, often accompanied by a reason as to why they arrived late (traffic, another appointment, etc). The apologies represent respect for the other person and for keeping them waiting, as their time was essentially wasted while they were waiting. For the individual in these cultures who is late, the pressure is increased when circumstances arise that keep them from getting to their destination by the agreed-upon time.

For people in the United States, and others in a task-oriented culture, saving time is one of the biggest values. The saying “time is money” showcases just how much that is true. The goal is to plan the job in advance, be efficient, and get the job done. Task-oriented cultures enjoy using time efficiently and try to plan their days (almost to the minute sometimes!) so that they will be able to fit the maximum amount of tasks and activities into each day. When those in a task-oriented culture have a meeting or an event, a time is set for when the event will happen and the people involved are committed to being there, ready to go, at that specific time. This is true even for casual meetings between friends. To keep people from a task-oriented culture waiting after the set time is to say “you are not important, so your time is not important. I don’t respect you or think you have anything more important to do than wait for me.” If you were late to a meeting in a task-oriented culture, apologies would immediately be made upon arrival, often accompanied by a reason as to why they arrived late (traffic, another appointment, etc). The apologies represent respect for the other person and for keeping them waiting, as their time was essentially wasted while they were waiting. For the individual in these cultures who is late, the pressure is increased when circumstances arise that keep them from getting to their destination by the agreed-upon time.

In her book, Foreign to Familiar Sarah A. Lanier shares an example of a different perspective on “being on time” from her experiences in Chile. She used to grow frustrated about having to wait for her friend close to an hour after they had agreed to meet at 2:00. Sarah’s friend, an event-oriented person, did not believe she was late, or that she needed to apologize when she arrived to find Sarah waiting. Sarah eventually realized that, in her friend’s mind, the appointment at 2:00 started when she began her journey to meet up with Sarah, not when she actually arrived. She was simply responding to the fact that it was 2:00 by starting her travel to the meeting. Event-oriented cultures have a tendency to react to what life brings instead of planning their days around being somewhere and doing something at a specific time. The value placed on experiencing the moment makes event-oriented cultures very spontaneous and flexible in their approach to life compared to the very structured lives of their task-oriented counterparts.

Take a look at an excerpt from Sarah’s book in which she gives an example of what a wedding would look like hosted by an event-oriented culture with task-oriented attendees:

Take a look at an excerpt from Sarah’s book in which she gives an example of what a wedding would look like hosted by an event-oriented culture with task-oriented attendees:

The event is a wedding. The location is Jamaica, Zimbabwe, Colombia, or the Philippines (an event-oriented culture). The wedding is to be at 2:00 pm. At 1:45 pm, four Norwegians and two Canadians show up to take their seats before the wedding starts. They find the church locked up and no one around… A bit worried that there really is to be a wedding, the (task-oriented) guests wait on the steps. At 1:55, a group of women arrive with flowers, and they unlock the church and start decorating. A choirmaster comes in a few minutes later and starts getting out choir robes. By 2:30, a few people arrive, hanging around and talking outside. The [task-oriented] guests have found seats by now and keep looking at their watches, becoming frustrated that the wedding is getting started late, and no one seems to care. What they don’t know is that at around two o’clock the bride started getting ready, the preacher started a meal with the groom’s parents, and a young man started his five-kilometer walk to the church. Stopped along the way by an old man, this young man takes as long as the old man wants to talk. It would have been dishonoring for him to tell the older man that he needed to hurry…

Around 3:45 pm, the bride and groom finally arrive, and the ceremony begins. By six o’clock, the wedding feast is in full swing. This [event-oriented] wedding was an event, and the event began at 2:00 pm. That was when people stopped what they were doing and began wedding activities – getting the church decorated, entertaining the groom’s family, and washing the children to get them dressed up for the occasion. (Pg 111-113)

As I’m sure you can imagine, the task-oriented guests were very frustrated and probably very confused. Task-oriented cultures have an expectation for an event to begin at the time announced – with visiting, chatting, and “behind the scenes” work happening before or after the event. These task-oriented guests expected everything to be ready and prepared before 2:00, with everyone in their places and the bride ready to start down the aisle as soon as the clock struck 2:00. However, to the event-oriented people, the wedding did start at 2:00, it just began with all the activity and preparation for it at 2:00 as well. In an event-oriented culture, the wedding ceremony is only a small part of the event, not the event itself.

Spontaneous Hosts Vs Planned Hosts

Often, hosting in a task-oriented culture is seen as a formal event and one which is taken seriously and planned for. In the United States, hours of cleaning and preparing usually occur before hosting guests in the home. Hospitality is a special occasion in task-oriented cultures and takes the host’s full attention to ensure that everything goes according to plan. For a guest to show up unannounced in a task-oriented culture could be seen as rude and could give the host anxiety. People in the US, and other task-oriented cultures, enjoy having time to themselves, adding it into their schedule each day. To suddenly be asked or forced to do something that was not in their original plan could completely disrupt their schedule and, therefore, their trusted and relied-upon structure.

In comparison, spontaneity is a part of hospitality in an event-oriented culture. For people from an event-oriented culture, a chance to show hospitality can happen at any moment, just as the young man showed the older man from the wedding example earlier. The young man was “stopped along the way by an old man” and he took as long as the old man wanted to talk because “it would have been dishonoring for him to tell the older man that he needed to hurry.” The young man showed spontaneous hospitality to the older man; it was not planned and there was no set time when it would end. The young man simply took as much time as was needed to talk to him, make him feel comfortable, and create a relationship with him. When hosting in their homes, people from an event-oriented culture don’t mind if someone just shows up. “Coming over will never interrupt them. They will continue cooking, playing with the kids, or watering the garden. You will just fit into whatever is going on at the moment” (Pg 73). They don’t need time to clean or cook before a guest comes and they also don’t have a concept of needing to spend time alone like those from a task-oriented culture do. For those in an event-oriented culture, hospitality is about relationships and there is always time for relationships.

Conclusion

While the structure and planning of task-oriented cultures can help avoid crises and may result in higher efficiency, it also could cost rich learning experiences and relationships that would have been the result of following spontaneity. The two different sides of time, task-oriented time and event-oriented time, each have something great and important to learn from the other. Bringing together two opposing approaches to time could be a beautiful thing! What could you practice to stretch your understanding of time and fit within the time culture of another person?