Based on: Sarah A. Lanier’s book Foreign to Familiar. McDougal Publishing: 2000.

“I’ve been lonely since moving here (the U.S), and now I know why. When people in the office would ask me if I wanted to go to lunch, I would say ‘no’ to be polite, fully expecting them to ask me again. When they didn’t and left without me, I thought they didn’t really want me along and had only asked out of politeness. In my culture, it would have been too forward to say ‘yes’ the first time. For this reason, I’ve had few American friends.”

~Foreign to Familiar by Sarah A. Lanier

Each culture has different values and practices that are expressed in daily living and how they relate to life, themselves, and each other. For this reason, members of different cultures can experience frustration and even conflict when experiencing a culture opposite from their own.

Each culture has different values and practices that are expressed in daily living and how they relate to life, themselves, and each other. For this reason, members of different cultures can experience frustration and even conflict when experiencing a culture opposite from their own.

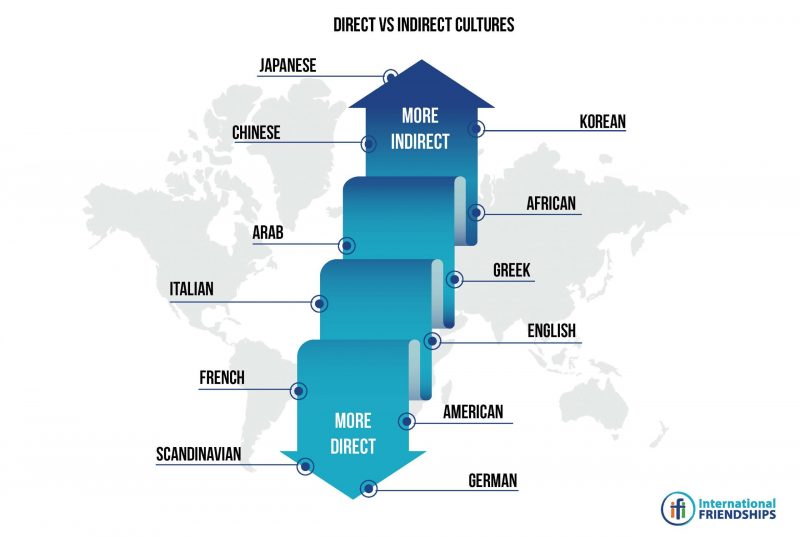

The book, Foreign to Familiar, by Sarah A. Lanier, paints a clearer picture of the many differences between cultures, one difference being how most cultures can be split into one of two categories: either a direct culture or an indirect culture*. When a person who uses direct communication and a person who uses indirect communication try to communicate, problems and misunderstandings can arise if the differences are not understood. Becoming educated on the differences in culture is especially important when working with internationals or in an international environment so that all parties can understand and communicate in a way that is harmonious.

People in direct cultures, like Americans, are more task-oriented and work toward honest and accurate communication, even if that means unintentionally offending someone. Alternatively, indirect cultures are more relationship-focused; their communication is focused on being friendly, avoiding giving anyone (including themselves) embarrassment, and being completely inoffensive. Below, are three common characteristics to watch out for when talking to someone from an indirect culture.

It’s All About Being Friendly

In a conversation, the person with direct communication is trying to get their point across, while the person with indirect communication is mainly focusing on the relationship aspect of the conversation. The indirect communicator is trying to be friendly, but the direct communicator is merely focused on whatever task is at hand. If the direct communicator walks into a store for a box of nails, they are likely going to ask the employee, “where can I find nails?” For the indirect communicator, this is going to seem extremely rude. In their case, they would first say, “Hi, how are you? Would you be able to help me?” And then, after a friendly atmosphere is established, they would ask “where is the hardware section?”

For another example, examine the conversation below between an American gentleman and a Yemeni (Middle East/Arab) flight attendant on a plane.

Flight Attendant: Excuse me, sir. Would you like coffee or tea?

American: I’d love to have a cup of coffee, please!

Flight Attendant: I’m sorry, we only have tea.

For the direct communicator who expects words to be accurate and mean what they say, the flight attendant’s answer is mind-boggling. However, for the Yemeni flight attendant who focuses more on the relationship than the facts, her words were merely a pleasantry, and definitely not meant to offend. In the indirect communicator’s world, words are often used as a means of establishing a pleasant atmosphere, even if the meaning of the words is not factual. The literal meaning of the words is not nearly as important as the connection established by their use.

For the direct communicator who expects words to be accurate and mean what they say, the flight attendant’s answer is mind-boggling. However, for the Yemeni flight attendant who focuses more on the relationship than the facts, her words were merely a pleasantry, and definitely not meant to offend. In the indirect communicator’s world, words are often used as a means of establishing a pleasant atmosphere, even if the meaning of the words is not factual. The literal meaning of the words is not nearly as important as the connection established by their use.

“Yes” or “No” Does Not Necessarily Mean Yes or No

In America, with its overabundance of direct communicators, you can mostly trust that when someone says yes or no, they really mean it and that there are no hidden meanings behind their words. In cultures with indirect communicators, this may not always be the case. Sometimes a “yes” may actually not be a factual yes, but instead a friendly interchange or socially required in their culture. Some indirect cultures will say “yes” when they really mean “no” in order to avoid embarrassing the asker, especially in a case where there is a third person present. One example might be if an American were to ask an Asian if they agreed with something. In order not to disagree with the American to their face (which would be seen as rude to Asian culture) they say “yes,” when in reality they really do not agree at all with what the American said. Another interesting example of this is one directly from Foreign to Familiar in which Sarah explains to a friend what it was like to grow up in Israel.

Sarah: I grew up in a variety of cultures. The Jewish and Arab cultures are vastly different.

Friend: How so?

Sarah: In the Jewish culture, you say what you think. It’s direct, and you know where you stand with people. The Arab culture, on the other hand, is much more indirect. It’s all about friendliness and politeness. If offered a cup of coffee, I say ‘no, thank you.’ The host offers it again, and I decline again with something like: ‘no, no, don’t bother yourself.’ He might offer a third time, and I’d reply, ‘no I really don’t want any coffee. Believe me.’ Then my host serves the coffee, and I drink it.

Friend: You’ve got to be kidding me!

Sarah: No really. You’re supposed to refuse the first few times. It’s the polite thing to do.

Friend: Then, what if you really don’t want the coffee?

Sarah: Well, then there are idioms you can use to say that you wouldn’t for any reason refuse their kind hospitality, and at some point in the future you’ll gladly join them in coffee, but at the moment you really can’t drink it.

Just as Sarah’s friend was surprised by the very different way the Arab culture spoke, the people of direct cultures find this roundabout way of doing things to be ridiculous. Many ask, ‘Why can’t they just say what they mean? Why can’t their yes be a yes and their no be a no?’ The goal of the indirect speaker is friendliness, not information. For these indirect cultures, trust is considered critical for survival and success; and friendliness is a foundation for relationships and trust.

Go Through a Third Party for Accurate Information

If the “yes” and “no” of indirect cultures cannot be taken at face value, then what is the best way to get the clearest and most accurate information? Take a look at this very intriguing example from Sarah’s book of a foreigner visiting an indirect culture asking where the nearest post office is:

Frustrated tourists in Turkey or the Philippines or some other hot-climate culture have asked this question many times and received a very friendly response and even directions. When they followed the directions, however, they discovered, much to their dismay, that the post office was not where they had been sent. Sometimes the village doesn’t even have a post office. Sometimes a person is trying to be helpful and can not bear to disappoint the questioner with bad news, so he or she gives a friendly answer just to create a friendly atmosphere. The answer may not be accurate at all.

So how do you get to the truth? The answer is to try the indirect approach- a third, independent party; someone with little to no involvement in the original communication exchange. When talking to someone from an indirect culture, always try to avoid direct questions so that the person being questioned is not embarrassed or ashamed for not having the correct answer. In the case of the mystery of where the post office is in town:

One method would be to ask a man on the street if he would ask the man on the corner if he knows where the post office is located. In this way, the man on the corner can be free to say to the messenger, “No, man, I haven’t a clue where it is.” He is free to say this because he is not disappointing a visitor to his country. He is just responding to the messenger. You will discover, sooner or later, that rarely does the direct approach result in the answer you are looking for.

One method would be to ask a man on the street if he would ask the man on the corner if he knows where the post office is located. In this way, the man on the corner can be free to say to the messenger, “No, man, I haven’t a clue where it is.” He is free to say this because he is not disappointing a visitor to his country. He is just responding to the messenger. You will discover, sooner or later, that rarely does the direct approach result in the answer you are looking for.

In this way, the asker gets a factual answer, and the person who answered the question faces no direct pressure or possible embarrassment from the asker. This also fits in numerous other situations such as if someone is wondering whether or not their music is too loud for someone else. A person from a direct culture would feel free to say, “Actually, it is really loud and it’s giving me a headache,” or perhaps even approach the music player first and say “it’s too loud.” For an indirect communicator, however, they are far more likely to say, “no, it’s fine,” than make the loud music seem like a big deal or an inconvenience. The best approach for the music player is to indirectly ask through another friend who would then ask the indirect communicator, “Hey Mario, what do you think of Jack’s music?” This may seem a very dishonest or sneaky way to find out information, but in cultures that speak indirectly, it is viewed as very acceptable. In this way, the truth is learned without causing any offense.

Neither indirect nor direct communication is intrinsically right or wrong. In all cases, when interacting with someone from a culture different from your own, it is important to take time to listen and understand how they communicate first before expecting a specific type of indirect or direct communication from them. Coming to recognize and understand what type of communication a culture values and practices can help avoid conflict and misunderstandings as well as help achieve effective communication!

*The difference between indirect and direct cultures is often considered a difference between hot-climate and cold-climate cultures. Typically, if a culture lives in a climate that is normally hot then they would be considered indirect communicators, and those living in a climate that is normally cold would be direct communicators. However, this formula isn’t exact.