Based on Sarah A. Lanier’s book Foreign to Familiar, McDougal Publishing: 2000.

I am in lovely Uganda. I was shown my room. It was simply furnished with a bed and a mosquito net. Next to my bed another mattress had been placed on the floor and a makeshift mosquito net tied to the window to cover it. My hostess said, “Here is your room, but don’t worry. I have put a person in here with you so you won’t have to be alone.”

~ Foreign to Familiar by Sarah A. Lanier (pg 68)

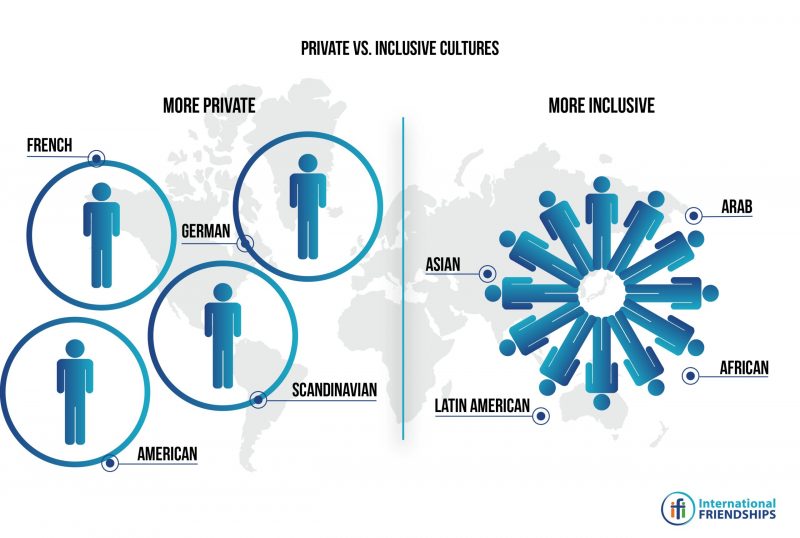

Privacy is of high importance in U.S. culture. The word “mine” is often one of the first words a child learns, and with it comes the ideas and feelings of ownership. Eventually, children learn about sharing their belongings, but the idea of owning something and being the one to choose to share it never goes away. In the U.S, and other direct or private cultures like it, people are expected to ask permission before borrowing something that belongs to another person. However, indirect or inclusive cultures see things a little differently.

In an inclusion culture, possessions are used freely by all. This means that food, tools, and even clothes are freely shared no matter who they belong to. In a culture such as this, it is not “I have” but “we have.” This can apply to time as well. Direct cultures covet their private time to themselves saying, “this time is mine,” while indirect cultures have almost no concept of alone time and choose to spend free time with others.

These differing cultural views concerning privacy can cause lots of misunderstanding while traveling internationally. Sarah Lanier, a consultant and lecturer on culture, breaks down the sometimes drastic differences between cultures in her book Foreign to Familiar. Most cultures can be broken down into one of two categories; either a direct or indirect culture. For more on differences between direct and indirect cultures, visit the previous article 3 Characteristics of an Indirect Communicator.

In the case of privacy and inclusion, direct cultures will typically fall into the category of a privacy culture while indirect cultures will typically fall into the inclusion culture category. Learning about the differences in cultures and how views of privacy can change from one culture to the next can help immensely while hosting internationals or even while traveling internationally yourself. Understanding differences in cultures will help avoid miscommunications that could damage the relationship.

Privacy Vs Inclusion

During her travels, Sarah discovered that her biggest sacrifice when traveling to indirect cultures would be in giving up her privacy and time to herself. Sarah initially was exhausted in indirect cultures because she never knew when she would be interrupted, but once she got used to it she began to understand the value that indirect cultures placed on inclusion.

Sarah initially was exhausted in indirect cultures because she never knew when she would be interrupted…

Read the excerpt below from Foreign to Familiar where Sarah realizes what a huge difference moving to an inclusion culture can make on feelings of isolation:

When I lived in Amsterdam, a common topic of discussion among colleagues was the loneliness of the city. I spent years trying to brainstorm with others on what to do about our feelings of isolation and lack of relationship.

Then I lived in Chile for nine months. At the end of that time, I realized I’d never met a lonely person. It was almost impossible to be lonely. People were always dropping in, settling into your kitchen while you cooked, and chatting away. If you wanted to be with people, you just walked out your door and started visiting. If you didn’t, you had to hide.

Downfalls of Structured Privacy

When indirect cultures visit direct cultures, it can sometimes be very lonely due to the fact that direct cultures are so private and reserved. Sarah experienced this very thing on her return to the United States. After living in Chile for nine months, living in a direct culture once again caused her feelings of isolation to return. One Sunday afternoon, she cooked up a whole bunch of food and then proceeded to call around to all of her friends to have dinner with her. One by one they all gave an excuse as to why they wouldn’t be able to come, most due to their need for privacy and planning ahead. That’s when Sarah realized one of the biggest reasons for loneliness in the well-organized city of Amsterdam. What they needed was a little more spontaneous relationship (indirect culture) and a little less structured privacy (direct culture.)

When indirect cultures visit direct cultures, it can sometimes be very lonely due to the fact that direct cultures are so private and reserved. Sarah experienced this very thing on her return to the United States. After living in Chile for nine months, living in a direct culture once again caused her feelings of isolation to return. One Sunday afternoon, she cooked up a whole bunch of food and then proceeded to call around to all of her friends to have dinner with her. One by one they all gave an excuse as to why they wouldn’t be able to come, most due to their need for privacy and planning ahead. That’s when Sarah realized one of the biggest reasons for loneliness in the well-organized city of Amsterdam. What they needed was a little more spontaneous relationship (indirect culture) and a little less structured privacy (direct culture.)

When indirect cultures visit direct cultures, it can sometimes be very lonely due to the fact that direct cultures are so private and reserved.

Due to her loneliness, Sarah went to a restaurant just to be around people. From her booth, she could hear Spanish being spoken. She missed the inclusion culture and figured that most Spanish-speaking people would be from an inclusion culture, so she greeted them and told them she had just returned from Chile and missed hearing Spanish. Just as she expected, the mother scooted over and patted the seat beside her.

Sarah settled into their booth like an old family member and they told her they were on vacation in the United States and had looked forward to this trip for years. However, she was the first American to extend a welcome to them since arriving. The Mexican family had been surprised at how private Americans seemed to be. “They were not complaining” Sarah added, “they were just thrilled to have an American relate to them the way they would relate to a visitor in their country.”

Permission to Interrupt Vs Automatic Inclusion

Direct cultures such as the U.S. value privacy. For someone to barge into a conversation halfway through or invite themselves to dinner would be seen as extremely rude in a private culture such as the U.S. People in a direct culture feel they have a right to privacy; whether it’s a conversation, a meal, or just a quiet space to themselves. In a direct culture, there is an automatic assumption of others’ need for privacy and so intrusions would be prefaced with a phrase such as “Do you have a minute?” or “Is this a good time to ask you a question?” In this way, people from a private culture show respect for others and their privacy.

In an indirect culture, everyone is automatically included in whatever is happening in their presence.

Automatic inclusion is one huge difference that indirect cultures present compared to direct cultures. This means that in an indirect culture, everyone is automatically included in whatever is happening in their presence. If a friend were to walk up mid-conversation, without even knowing what the conversation is about, in an inclusion culture they would automatically be included. The conversation would not be presumed to be a private one, and a friend may feel free to walk up and join them. This would be the same for a meal, a sport being played, a show being watched, or almost anything else. Sarah says, “In Chile or Egypt or other [indirect] cultures, I can assume I can join in with whatever is going on in my presence, in plans being made, and in food being shared.” Read the excerpt below from Foreign to Familiar about how a private evening Sarah thought she was going to have with a friend turned into an inclusive event:

I was invited to the home of an American friend for dinner in Chile. It had been over a year since we had seen each other, and our plan was to catch up on news of mutual friends and share photos. I, for one, was expecting an evening of private conversation.

While we were still eating, a knock came on the door, it opened, and a man came in. He pulled up a chair and joined us. We forgot our previous conversation and talked with this man about local news. Then another knock on the door announced yet another visitor, and this visitor too joined us and the subject of conversation was once again changed. The two visitors stayed until midnight, and we thoroughly enjoyed their company. Our own plans were forgotten.

What seemed strange for me was the fact that my American friend thought nothing of this intrusion. He had lived in Chile so long that he no longer considered our visit a private one. It had become, for him, an inclusive event.

In an indirect culture, there is little distinction between who is a part of an event and who is not, at least on a social level. When people from an inclusion culture travel to a culture where people are more private, they are often shocked to learn automatic inclusion is not practiced there. Privacy seems “exclusive” to a person who practices inclusion culture and it is hard for them to understand a more private nature.

“We Have” Vs “I Have”

Similar to how indirect cultures live by the concept of “automatic inclusion,” inclusive cultures are also built upon the principle of sharing. In an inclusive culture, there is no “I have this” and “you have that;” there is only “we have.” This concept can be applied most directly to food. People in an inclusive culture would never take out a sandwich in front of others and not offer to share it. There is a saying in Japanese, “Even if you only have a single pea, you divide it up equally according to the number of people in the room.” There is no concept of “will there be enough for everyone?” The important thing is that whatever is available, is shared.

Similar to how indirect cultures live by the concept of “automatic inclusion,” inclusive cultures are also built upon the principle of sharing. In an inclusive culture, there is no “I have this” and “you have that;” there is only “we have.” This concept can be applied most directly to food. People in an inclusive culture would never take out a sandwich in front of others and not offer to share it. There is a saying in Japanese, “Even if you only have a single pea, you divide it up equally according to the number of people in the room.” There is no concept of “will there be enough for everyone?” The important thing is that whatever is available, is shared.

In an inclusive culture, there is no “I have this” and “you have that;” there is only “we have.”

On a bus ride with other delegates, Sarah had brought a lunch that could be shared; having learned about inclusion cultures. When two European men took out their own lunches and began to eat, Sarah got hers out too. Read the excerpt from her book below to see the differences in cultures when it comes to the “we have” vs “I have” principle:

I offered the men some grapes. They said, “Thank you, but we brought our own lunches.” They also refused the cookies. Then I got up and offered the grapes to others around me on the bus: Africans, South Americans, and Asians. They all happily accepted the offering and then pulled out their own food to share. Soon we were handing around bags of dried figs, potato chips, hunks of bread, cheese, and other items. We had a feast that day.

The two Europeans enjoyed their own lunches, but they missed the more important event. It wasn’t as much about food as it was about sharing with one another, leaving no one out. It took care of those who didn’t have anything by including them in the group. Because everyone shared, we were not aware of the “haves and the have-nots.” They were covered by the community. The inclusion value of [indirect] cultures means that no one is left out, no one is lonely.

In direct cultures, possessions are treated as the personal responsibility of the individual who owns them.

By this same principle of “we have,” inclusion cultures also think of any possessions as “ours” not “mine.” In direct cultures, possessions are treated as the personal responsibility of the individual who owns them. From a young age, children are taught to take care of their own possessions and they have the right to decide whether to share or not share. Sometimes, people will even label food or possessions as their own in order to further avoid anyone taking or using them. In an inclusion culture, this is reversed, saying “We have a guitar,” “we have food in the refrigerator,” “we have tools to use,” and “we have a car,” regardless of who paid for the items. Furthermore, this “we” will include everyone currently in the house, not just the people who live there.

Sarah witnessed a man seeking a ride from an American couple on their way into town. Sarah knew that in an inclusive culture, if a car was going into town and there was a seat available, she could ask to go along. The American couple turned down the man asking for a ride, wanting time to themselves. Their decision was based on a need for privacy, but the man felt rejected. To people in an inclusive culture, it is never “I am going into town,” it is, “We have a ride to town.” The privacy culture Americans just didn’t understand that.

Another example of misunderstandings in “we have” vs “I have” thought processes that Sarah has seen involved a Chinese student arriving in Hawaii for school. His American roommates had already deposited their luggage in the room and left. The Chinese student, coming from an inclusive culture where everything is shared, began to try on his roommates’ clothes. In the worldview of the Chinese student, it was not “you have a suitcase full of clothes, and so do I,” but “There are clothes here to be worn. Let’s see which ones fit me best.” When his private culture North American roommates returned to find him trying on their clothes, they were outraged at the invasion of their privacy. This left the Chinese student confused and shamed. He had no concept of how individualistically Americans viewed their things. One of his first introductions to America turned out to be one of trauma and wounding because of a misunderstanding between cultures.

Another example of misunderstandings in “we have” vs “I have” thought processes that Sarah has seen involved a Chinese student arriving in Hawaii for school. His American roommates had already deposited their luggage in the room and left. The Chinese student, coming from an inclusive culture where everything is shared, began to try on his roommates’ clothes. In the worldview of the Chinese student, it was not “you have a suitcase full of clothes, and so do I,” but “There are clothes here to be worn. Let’s see which ones fit me best.” When his private culture North American roommates returned to find him trying on their clothes, they were outraged at the invasion of their privacy. This left the Chinese student confused and shamed. He had no concept of how individualistically Americans viewed their things. One of his first introductions to America turned out to be one of trauma and wounding because of a misunderstanding between cultures.

Are Children Included?

When traveling in privacy cultures, a common mistake made by those from inclusive cultures is to assume that their children are included in invitations. For an inclusive culture, Adults-only events are unfamiliar and even strange. Typically in an indirect culture, any gatherings outside the workplace are family gatherings which automatically include children – noise and all. This can be frustrating for the Americans or Europeans, as they feel the distraction of children running in and out takes away from the quality of the event.

When traveling in privacy cultures, a common mistake made by those from inclusive cultures is to assume that their children are included in invitations. For an inclusive culture, Adults-only events are unfamiliar and even strange. Typically in an indirect culture, any gatherings outside the workplace are family gatherings which automatically include children – noise and all. This can be frustrating for the Americans or Europeans, as they feel the distraction of children running in and out takes away from the quality of the event.

Therefore, when visiting direct cultures, people from an indirect culture should make a point of clarifying whether or not an invitation includes children. To show up with children at someone’s home for dinner, and then discover plates set only for the adults, is an unnecessary embarrassment that could be quickly solved through clarifying. Parents from indirect cultures also need to keep in mind that in cases such as weddings, where children are invited, the children are expected to stay with their parents, and if they make noise, they should be removed.

Conclusion

Understanding the differences between indirect and direct cultures can be monumental in helping to achieve good relationships with someone from a culture opposite your own. Whether you are traveling internationally yourself, or hosting an international, it is always wise to find out what their cultural practices and beliefs are before assuming that they are the same as yours. In the case of privacy differences between cultures, it may be wise to have a discussion regarding this almost immediately in order to avoid any misunderstandings or embarrassments. Always be clear and be sure to ask questions to make sure you understand. Then, set boundaries that you and they can feel comfortable with. This way, your international friendships will be built on an understanding of each other’s cultures and practices instead of hurtful misunderstandings!